The LTA, LSA, and LSDBA: Looking back to previous Budgets and how pension reforms work now

This article is intended for financial services professionals only. None of the information contained in this article should be received as advice. Pensions are a complicated area of financial planning and IPM suggests that financial advice from a suitably regulated financial adviser is sought before an individual takes any action in respect of their pension savings.

With all this talk of the Budget, it has got us thinking about Budgets past.

For a long period, there were few changes in pension legislation, dating back to how defined contribution (DC) pensions could be distributed upon death in the mid-2010s.

This all changed quite suddenly (and unexpectedly!) in the Spring Budget of 2023, when then-chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced the removal of the Lifetime Allowance (LTA).

Of course, we now know that wasn’t quite the case. The famous “devil in the detail” after the Budget announcement revealed that the LTA charge was to be removed from April 2023, with the full removal of the LTA coming in April 2024.

In its place, a range of terms, acronyms, and limits were announced. In particular, the Lump Sum Allowance (LSA) and the Lump Sum Death Benefit Allowance (LSDBA) were introduced.

- The LSA is an upper limit of the amount of tax-free lump sums an individual can withdraw in their lifetime

- The LSDBA is an upper limit on the amount of tax-free benefits that can be paid to nominated beneficiaries in the event of the death of a scheme member.

But why were any of these upper limits – the LTA, LSA, or LSDBA – needed in the first place? To look at how we got here, it is worth considering what came first.

Looking back to pension simplification in 2006

For those of us old enough to remember, 6 April 2006 was a significant day for pensions. Also known as “A-Day”, this date was the launch of “pension simplification”, an attempt to streamline the various forms of pensions legislation that had built up over the years into one simplified format.

It would be easy to mock this attempt with the benefit of hindsight. But it should be remembered that, despite subsequent revisions to pension legislation, it could be argued that the pension landscape is in a much better position than if A-Day had not taken place.

Before A-Day, for DC schemes such as SIPPs, the maximum an individual could contribute was determined by a percentage of their earnings, with that percentage determined by their age. The maximum contribution for someone over the age of 60 was around £37,000 gross.

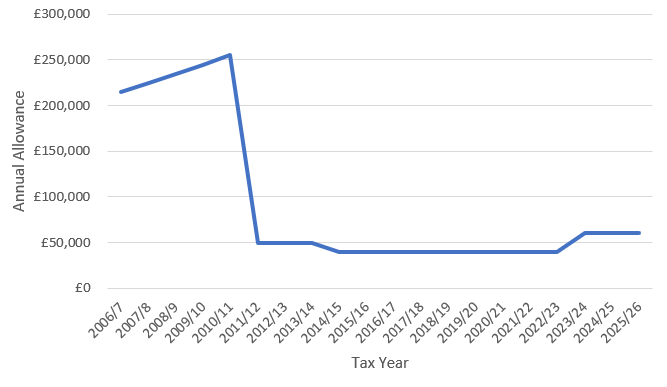

After April 2006, this changed. The new term “Annual Allowance” was introduced. An individual would now be able to contribute up to the lower of the Annual Allowance or 100% of their earnings and receive full tax relief. For employer pension contributions, there was no test against earnings.

For 2006/07, this was set at £215,000, and then increased by £10,000 a year until 2010/11, when the Annual Allowance was set at £255,000. Quite the jump from £37,000 pre-2006!

The government realised that this was probably a bit too generous. So, in 2011/12, we saw a drop in the Annual Allowance to £50,000. Since then, it has hovered around this level, bringing us to the £60,000 we are familiar with today.

When the government announced the increase to the Annual Allowance, someone realised that they had probably better put a total cap on these contributions. This led to the introduction of the LTA.

The LTA was an upper limit on the tax-efficient savings someone could make across all their pension pots.

At the point of drawing benefits, the total pension savings would be tested against the LTA. If their savings exceeded this limit, there would be tax consequences, which varied depending on whether the benefits were taken as a lump sum or as income.

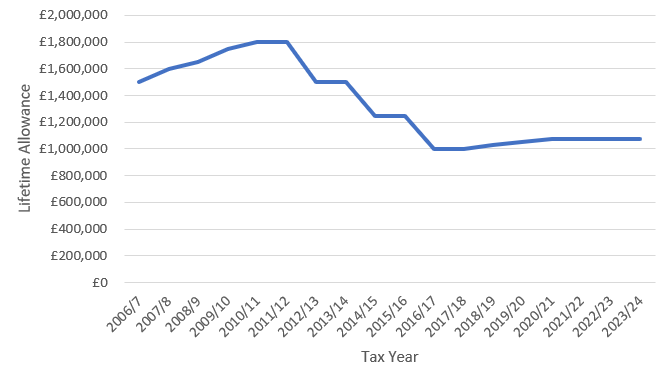

Starting in 2006/07, the LTA was set at £1.5 million. Like the Annual Allowance, the government had helpfully confirmed the LTA threshold for the next five years. For 2011/12, this was set at £1.8 million.

As with the Annual Allowance, the government probably thought that an ever-increasing LTA was a bit too generous. So, they announced a downward reversal from 2012, dropping the LTA to £1.5 million in 2011/12, all the way down to £1 million in 2018. This then began to creep back up to the limit we had in 2023 of the very catchy and memorable £1,073,100.

The LTA could be complicated, especially when the government introduced various levels of LTA protection to avoid penalising those who had contributed to their pots before reductions in the threshold. But after almost 20 years, advisers and providers understood it.

That’s no doubt what made the announcement in the 2023 Budget all the more surprising. At first, the removal of the LTA sounded like an end to the complications. But with the introduction of the LSA and LSDBA, it quickly became clear there would be new rules for advisers and providers to consider.

Lump Sum Allowance

The LSA puts an upper limit on the amount an individual can receive from their pensions tax-free in their lifetime. The standard LSA is set at the catchy £268,275. Why? Because this is 25% of the old standard LTA (£1,073,100), which was the previous cap on tax-free cash from pensions.

For individuals who have not taken any benefits prior to 6 April 2024, dealing with the LSA is fairly straightforward. If you have a client who has benefits that total £500,000, for example, the maximum amount of available tax-free cash is 25% of the fund value at the point of a relevant benefit crystallisation event (RBCE) – so in this instance, £125,000. This is below the LSA, so no issues here.

However, if we consider someone who has a pension pot valued at £1.5 million, the LSA will come into play. 25% of £1.5 million is £375,000, above the LSA of £268,275. As a result, in this case, the maximum that this individual would be able to take as a tax-free lump sum is the LSA of £268,275.

Not ideal for the client with £1.5 million, but still all fairly easy to understand and explain to clients. Where clients have drawn benefits prior to 6 April 2024, however, things start to become a little more complicated. Read our case study to find out even more about this.

Lump Sum Death Benefit Allowance

The LSDBA is set at £1,073,100, the same level as the LTA when it was abolished. As the name suggests, only lump sum death benefits are tested against the LSDBA.

It is important not to overcomplicate matters when we start to think about the LSDBA; the death benefit position as it currently stands is the same as it always has been. For most clients (that is, those below £1 million in pension savings), this will not be an issue. It’s only when benefits exceed the LSDBA that we need to start thinking about these rules.

Let’s think about calculating the available LSDBA when a relevant lump sum is to be paid to the nominated beneficiaries of the deceased.

Any relevant lump sums previously taken since April 2024 by the original scheme member should first be deducted. That includes a pension commencement lump sum (PCLS) and the tax-free element of uncrystallised funds pension lump sum (UFPLS) payments that have been tested against the LSA. Again, this is fairly straightforward.

Transitional rules apply where benefits have been taken before 6 April 2024. Further consideration is also required where an age 75 LTA test was undertaken, and then a benefit crystallisation event (BCE) took place before April 2024. You can also read more about this in our case study.

Transitional tax-free allowance certificate

One of the many challenges for this new regime is to account for those individuals who have previously partially crystallised some benefits but have some lump sum remaining and now wish to access this.

The pre-April 2024 process saw tests against the LTA on a percentage basis. From April 2024, we are testing against monetary figures (the LSA and the LSDBA). HMRC issues standard calculations which need to be carried out for individuals who had previously partially crystallised benefits before April 2024.

However, these calculations left some people in a worse position had the regime not changed. As a result, people can apply for a transitional tax-free allowance certificate (TTFAC) if they feel the new rules would leave them with a lower LSA or LSDBA than otherwise would have previously been the case when testing against the LTA.

There are several times when an individual may benefit from a TTFAC. Whether this is the case will depend on an individual’s specific circumstances. While not exhaustive, some of the common times a TTFAC may be of assistance include:

- When the previous calculation took place while the LTA was under £1,073,100 – so between 2016/17 and 2019/20

- Where an individual was in a defined benefit (DB) scheme but did not commute their full tax-free lump sum entitlement

- Where someone is over the age of 75 and has unused funds.

An individual must request a TTFAC before the first relevant BCE from 6 April 2024; otherwise, the standard calculation will apply. Individuals with registered tax-free cash rights under enhanced or primary protection cannot apply for a TTFAC.

Also, we appreciate that as time progresses, we will see fewer of these scenarios. It is not possible for those individuals who drew benefits from a pension scheme prior to April 2006 but not between April 2006 and April 2024 to apply for a TTFAC, as there was no LTA to test against at this time.

Read our case study to see some scenarios where the standard calculation is used, and the impact of applying for a TTFAC.

Get in touch

If you want to have a chat about the potential of SIPPs for your clients, or any other aspects of pension planning, please contact us. Email info@ipm-pensions.co.uk or call 01438 747151.